Inclusive and accessible to all? An evaluation of children’s picturebooks and their representation of physical disability.

Caroline Linnea Oestergaard

BA (Hons) Magazine Journalism & Publishing

London College of Communication, University of the Arts London

May 2019

ABSTRACT

In an investigation into how children’s picturebooks represent and include physical disability, the researcher develops a background understanding of diversity and disability as a whole, whilst further investigating the children’s publishing market, developing knowledge of how children’s picturebooks are written.

Primary research was conducted to support the dissertation, finding a low percentage of books featured disability during an observational analysis in Waterstones’ Piccadilly store. Further development came through a content analysis of 17 children’s picturebooks, specifically including disability as a close part of their visual or linguistic storyline. Despite not being able to conclude any growth or decline in the availability of these books, the researcher is able to assess what entails a respectful and well represented article; commenting on the accessibility of these type of books. Finally, interviews with a variety of key figures assess opinions on how physical disability is represented within the children’s picturebook market, concluding that a more diverse effort needs to be made to better represent all physical disabilities. Overall, the industry must become more aware of how and when physical disability is used in order to make it more commonplace whilst remaining considerate and appropriate, either through the main narrative or incidental inclusion, within children’s picturebooks.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A big thank you is first and foremost granted Frania Hall, without whose guidance, patience and endless knowledge this dissertation would not exist. Thank you for supporting this idea, for developing it with me and for making a concrete effort to make sure I was able to carry it through.

I would also like to thank Bridget Martin, Beth Cox, Alexandra Strick and Shaila Abdullah for their kindness and for taking time out of their busy schedules to answer my questions.

To Nick and Sue for proof reading. To Jack for the neverending support, love and for always being there.

CONTENTS PAGE

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Rationale

1.2 Scope

1.3 Structure

CONTEXT

2.1 The social and medical models of disability

2.2 Definitions of physical disability

2.3 The children’s publishing industry

2.3.1 Scale of the UK’s children’s books market

2.3.2 The developmental context of children’s literature

2.4 Definition of picturebooks

LITERATURE REVIEW

3.1 The value of children’s literature

3.2 Diversity in children’s literature

3.2.1 Why diversity in children’s literature is important

3.2.2 Representation of minorities within children’s literature

3.3 Disability in children’s literature

3.3.1 Representation

3.4 Language used to describe disability in children’s literature

3.4.1 ‘People first’ language

3.4.2 Acceptable and unacceptable language

3.4.3 Visual language

METHODOLOGY

4.1 Research goals

4.2 Research design methods

4.2.1 Observational analysis

4.2.2 Content analysis

4.2.3 Interviews

4.2.4 Overall combination of analytical approaches

4.3 Consent Ethics

FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS

5.1 Theories

5.2 Observational analysis

5.3 Contents analysis

5.4 Interviews

5.4.1 Representation

5.4.2 Commercial

5.4.3 Visual language and representation

5.4.4 Incidental inclusion

5.4.5 Future prospects

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

APPENDICES

Appendix A: Observational analysis tables and findings

Appendix B: Observational analysis photographs

Appendix C: Content analysis tables and findings

Appendix D: Content analysis photographs

Appendix E: In person interview transcript

Appendix F: In person interview consent form

Appendix G: Online email interview 1

Appendix H: Online email interview 2

1. INTRODUCTION

The aim of this dissertation is primarily to review and analyse to what extent the publishing industry includes physical disability within children’s picturebooks and how accessible these books are to the public. The researcher will investigate what is currently being done to include disability, how that is being reflected within current picturebooks and will be testing these theories through first person research.

1.1 Rationale

The representation of physical disability within children’s picturebooks was chosen as this is perceived to be one of the minorities that is least represented within this field. By conducting research around this topic, the researcher will be able to analyse and review the level of inclusion within the literature. Furthermore, in order to build up a comprehensive understanding of the key research question, an evaluation of specific theories around the inclusion of disability within all children’s picturebooks will be undertaken. In addition, an analysis of how characters with disabilities are represented, and whether those representations are respectful and accurate will be considered. Ultimately this will enable the researcher to provide greater conclusive evidence in the final chapter.

1.2 Scope

This study will focus solely on physical disability in order to narrow the field of research, allowing for the specific areas to be tested through both illustration and written language. By excluding other, non-physical disabilities such as learning differences and other mental disabilities, the researcher hopes to assess how these physical attributes take effect through books that use language and image in equally important quantities.

To develop the study further, the researcher intends to assess how diversity, especially physical disability, is represented in culture, and how that impacts inclusion within publications. As part of the contextualisation of this topic, the researcher will lay out and review definitions of disability, through physical, social and medical forms, setting precedents for how these items should be addressed in the remainder of the research. Furthermore, the current children’s literature market and structure will be reviewed, whilst contextualising how picturebooks are placed within the wider remit of children’s literature. Upon understanding the placement of these formats of books, a review of the publishing industry will be undertaken, with focus on children’s literature and picturebooks; this review will supplement and inform later conclusions.

1.3 Structure

The literature review will frame this dissertation by highlighting the current theories around children’s literature, whether picturebooks are important, the inclusion of diversity, representation of disability and the use of language surrounding disability. Developing this further, the methodology will review the research design and the methods used in order to conduct the necessary research for this dissertation. Analysis of the collected data and findings will be implemented to fully review the hypothesis enabling conclusions to be drawn from the collective findings of this research project. Reflecting on these findings will allow the researcher to pose recommendations to the publishing industry on how best to continue developing understanding and inclusion of physical disability within children’s picturebooks.

2. CONTEXT

2.1 The social and medical models of disability

Disability can be defined in both social and medical terms, both fundamentally drawing on comparisons to a non-disabled person and their quality of life. In the case of the medical model, a disabled person would be someone whose “impairment has such a traumatic physical and/or psychological impact upon individuals that they are unable to achieve a reasonable quality of life by their own efforts” (Barnes, 1991). In contrast, the social model “addresses the barrier to full participation in society caused by the practical, environmental, attitudinal or administrative framework of that society.” (Saunders, 2004). A medically disabled person is not necessarily considered socially disabled if the person is able to go through their life unhindered. To illustrate, a wheelchair user has the ability to manoeuvre around in everyday environments if made possible by lifts, ramps and accessible entrances. By the medical definition, they would be considered disabled as a result of their need to use a wheelchair. However, they would only become disabled under the social definition when they are no longer able to access environments through lack of accessible assistance; in this instance a person may be deemed disabled by both the medial and social definitions (Saunders, 2004).

These two key definitions could prove challenging when reaching a clear definition later in the research. By assessing disability against two slightly different definitions, it could be the case that in some instances a person may only be either medically or socially disabled. This is worth considering when reviewing featured instances of disablement within analytical aspects of the research, as a book may not fully express the level of disablement within its content.

2.2 Definitions of physical disability

Disability encompasses a wide spectrum of diagnoses and capabilities that affect people differently; both medically and socially. There is no singular definition of disability; although the phrasing in each definition is different, the underlying meaning remains closely the same. Each definition can focus on a specific range of disabilities, some could be more focused on mental disorders whilst others can target physical impairments.

In UK law: “You’re disabled under the Equality Act 2010 if you have a physical or mental impairment that has a ‘substantial’ and ‘long-term’ negative effect on your ability to do normal daily activities” (Gov.uk, 2019a). The definition allows for a broad interpretation of what it means to be disabled, which could be perceived in a positive manner as it grants greater scope for disability inclusion. However, it may also result in uncertainties between what is considered a disability in the eyes of the UK Government.

Conversely, Global Public Inclusive Infrastructure (GPII), who aim to ensure anyone who encounters accessibility barriers due to disability is able to access and use the internet as a resource, defines physical disability as: “the long-term loss or impairment of part of a person’s body function, resulting in a limitation of physical functioning, mobility, dexterity or stamina” (GPII DeveloperSpace, 2019). This is a clearer definition than that of the UK Government, as it lists specific limitations that cover physical disablement. People with some mental disabilities may also be defined as being physically disabled under the GPII definition, for instance people with severe autism where physical symptoms may present themselves. However, people with visual or hearing impairments, conditions that do not show any physical symptoms, or necessarily limit the person’s daily functions, are still considered physically disabled by the definition.

It can be seen that, further to medical and social definitions of disability, there is also a range of ambiguous definitions of what it means to be physically disabled. It could be concluded that the GPII and UK Government’s align with medical and social definitions independently. The GPII focused on the physical disablement and “impairment of part of a person’s body” (GPII DeveloperSpace, 2019), whereas the UK Government defines physically disabled on a social level through one’s “ability to do normal daily activities” (Gov.uk, 2019a). These broad definitions further add complexity to defining physical disability within children’s picturebooks during the research phase, therefore this study will only focus on physical disability as opposed to mental. Furthermore, in order to focus on the wider range of alternative disabilities, people with common minor disablements, such as the use of glasses or a walking stick as a result of age will not be considered.

In this dissertation, when the researcher references physical disability, this is not necessarily something that ‘disables’ ability to function, but includes any physical impairment irrespective of the effect on ability; hence defining a hybrid and combination of both medical and social disability.

2.3 The children’s publishing industry

2.3.1 Scale of the UK’s children’s books market

In order to acknowledge the extent to which disability is included in picturebooks, it is essential to understand the scale of the children’s book market. In 2017 the combined sales of UK children’s books, both physical and digital, was £354 million (Publishers Association, 2017). Of this, the market value for UK children’s books has increased 3%, from 21% in 2013 to 24% in 2017, when compared to the wider book publishing market. This is largely down to physical sales, as 94% of children’s books were sold in print form in 2017, compared to the remaining 2% and 4% representing audiobooks and Ebooks/Apps respectively (Egmont, 2018).

Within the children’s market specifically, picturebooks represented 18% of the overall sales in the UK in 2017, which is consistent with 2016 sales and only 1% lower than 2013 – 2015. This is the second largest share, only topped by children’s fiction at 36% in 2017 (Egmont, 2018). 64 million children’s books were sold in 2017 as calculated by Nielsen Bookscan. However, it is estimated that a further 36 million new children’s books were sold by unmonitored sellers such as value shops, educational purchases and independent booksellers (Egmont, 2018).

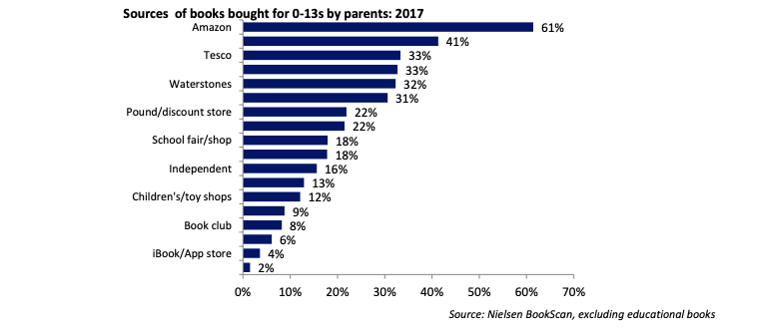

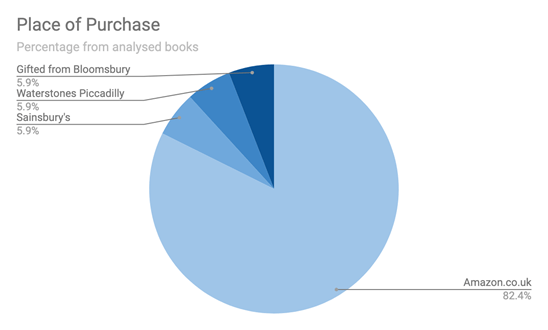

In analysing where children’s books are purchased, it can be seen that Amazon is the leading seller of children’s books (see Figure 2.1), with 61% of all books sold on Amazon were bought for 0-13 year olds (Egmont, 2018). The source of children’s books purchased is worth observing as this may be reflected by the researcher during the process of collecting relevant books for this dissertation.

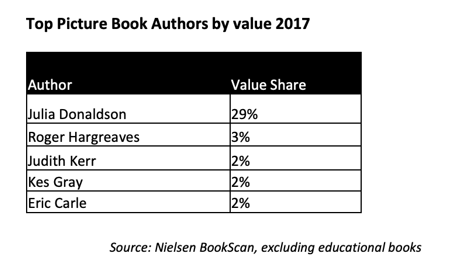

In 2017 there were 9115 children’s books published in the UK, of which 2003 were picturebooks (CLPE, 2018, p. 5). These books were published by 675 authors with Julia Donaldson, author of The Gruffalo, taking 29% of the picturebook market value share, compared to Roger Hargreaves, author of the Mr. Men and Little Miss series, who ranked second with 3% (Figure 2.2). This shows that the value share amongst picture book authors is heavily weighted to Donaldson, compared to the remaining authors. Whilst the table shows that there is only a few leading figures within picturebooks, this could mean it could be difficult to gain widespread recognition as a small author writing about disability. Furthermore, it also gives the opportunity for writers such as Donaldson and Hargreaves to introduce disability to an already established audience.

2.3.2 The developmental context of children’s literature

There are many different genres and formats of children’s books, each applying to a specific age range. Since, in many cases, books are something children grow up with, it is important to create books that align with the level of comprehension of the child as they grow (Backes, 2014).

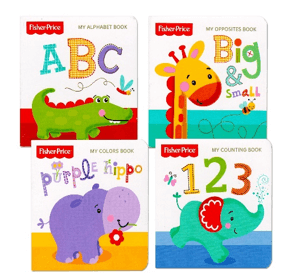

For infants and toddlers there are board books, which are made up of a small number of pages mounted on heavyweight cardboard (see Figure 2.3). As the children are too young to understand stories at this point in their life, these books feature simple elements such as pictures of animals, shapes and colours (Backes, 2014).

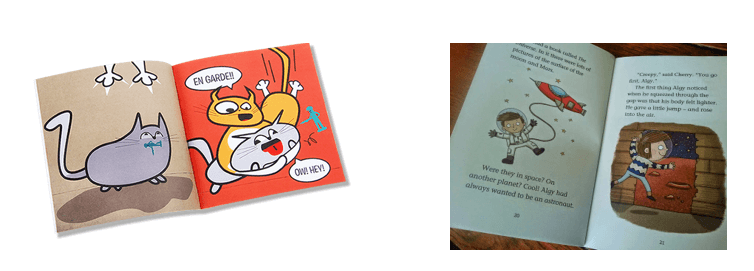

Picturebooks are typically 32 pages in length, with the narrative and language reflecting the reading, comprehension and target age of the child; typically anywhere between the age of two and eight (Backes, 2014). Picturebooks, as seen in Figure 2.4 are mainly intended to be read aloud to a child by an adult, giving the child the chance to read along with them by using the illustrations as interpretation, but can also be read by children starting to read (Salisbury, 2004, p. 74-75).

Following on from picturebooks, easy readers, as seen in Figure 2.5, are created for children who are developing their reading skills. By definition, these would fit under the umbrella term ‘picturebook’ as they too contain colourful illustrations and pictures to accompany the simplistic storyline. The only differences are that easy readers share the same rectangular portrait format of traditional books and can be between 32 and 64 pages long (Backes, 2014).

Transitional books are aimed at ages six to nine and are the next progression after picturebooks and easy readers. These differ from easy readers, because the books are longer and images and illustrations are typically black and white and feature every few pages. Following on from this, transitional books introduce a more complex sentence structure, beginning to split the book into chapters and heavily reducing illustrations to instead focus on the written word. These are ideal for seven to 10 year olds. As the children develop their literacy skills into Key Stage 2, age seven to 11 (BBC, 2019), books appropriate for that age get longer, contain more sophisticated storylines and begin introducing minor plot twists, as well as secondary characters. Finally, young adult books concentrate towards teenagers and young adults. These books are much longer, contain multiple plot twists, greater depth of secondary characters and tackle themes relevant to the struggles of teenage life (Backes, 2014).

From these definitions and categories, it can be seen there is a wide range of books designed for any age through childhood and adolescence. Overall, the ages accredited to these types of books are only a guide to the reading age of a child (Reading Chest, 2019). Picturebooks shape the middle section of children’s book development, the key area that this dissertation will focus on.

2.4 Definition of picturebooks

There are numerous picturebook definitions including the widely recognised one by Barbara Bader:

“A picturebook is text, illustrations, total design; an item of manufacture and a commercial product; a social, historical document; and, foremost, an experience for a child. As an art form it hinges on the interdependence of pictures and words, on the simultaneous display of two facing pages, and on the drama of the turning of the page. On its own terms its possibilities are endless”

(Bader, 1976)

There is a point for debate about whether ‘picturebook’ should be spelt using as one or two words. Bader’s reference to “interdependence of pictures and words” (Bader, 1976) realises the content of the product within its naming. This means that where the pictures and words are created together as one entity, ‘picture’ and ‘book’ should be combined into a single word. In contrast to this, the two-word setting “picture book” can refer to two independent pieces of work, for instance text, then pictures, being created for the purpose of being combined (Van Der Linden, 2016).

This dissertation will be using the one word phrasing ‘picturebook’, in line with Bader’s definition and to follow other leading commentators in the field. This construct is not necessarily followed by all therefore some references may refer to it as a two-word term.

3. LITERATURE REVIEW

3.1 The value of children’s literature

Children’s literature can be an important part of childhood, where it has a crucial part in socialising a child and introducing them to things outside of their day-to-day life. It can teach “the nature of the world, how to live in it, how to relate to other people, what to believe, what and how to think” (Evans, 1998, page 4-5); books speak values and “explore our common humanity” (Myers, 2014).

Alongside a child’s development, the relationship parents and guardians have to a child’s connection to literature can also be crucial in the early years. It has been shown that parents taking time to read books with their babies and children will have an advantageous impact on their children’s language comprehension, growth and expression, as well as their reading and writing skills and later enjoyment of books (Gamble, 2013). It has also been confirmed that children talking about the stories they read in picturebooks aids the development of their comprehension of human traits and behaviours (Saunders, 2004), highlighting how critical it is to start a dialogue with a child about the stories they read.

According to Crippen (2012),

“Children’s literature is valuable in providing an opportunity to respond to literature, as well as cultural knowledge, emotional intelligence and creativity, social and personality development, and literature history to students across generations. Exposing children to quality literature can contribute to the creation of responsible, successful, and caring individuals”.

Likewise, one of the most important things about children’s books is the channel they provide for children to learn about themselves and others through culture and heritage (Evans, 1998, p. 5). In other words, encouraging children to be understanding and accepting of the ways other people may differ from themselves. This is particularly important when concerned with acceptance, be that cultural, religious or sexual. To fully understand and accept views that may differ from one’s own, empathy is required towards another’s situation (Norton, 2010 cited by Crippen, 2012); books, therefore, can be a way to help instil this.

3.2 Diversity in children’s literature

3.2.1 Why diversity in children’s literature is important

Books have the power to shape the minds of those reading them, which is why it is important that the content is good, diverse and inclusive (Monoyiou & Symeonidou, 2015). Koss (2015) argues that as children’s literature plays an important part in the way a person views themselves, if children are able to mirror themselves in a character in a book, it sends a message that they are not alone, that they are understood, and ultimately that they belong in the society in which they live. As a result, representation of all diversity, be that race, gender, religion, disability and more, is important to allow the young reader to fully connect with the content. Conversely, it can be extremely damaging if children are not able to identify with book characters, as the message it sends is that their lives and stories are not important, which could affect their self-image and sense of belonging (Willett, 1995, p.176 cited by Koss, 2015, p. 32). Increasing the level of diversity in children’s literature is, therefore, extremely important in order to normalise different cultures, people and realities within the UK’s society, allowing children to grow up feeling valued (CLPE, 2018, p. 9).

There is a challenge facing the publishing industry to “redress imbalances in representation” (CLPE, 2018, p.9) as to ensure inclusion of all, not as a deed of charity or political correctness, but as a “necessity that benefits and enriches all of our realities” (CLPE, 2018, p.9). With this in mind, actions are being taken by children’s author Ade Adepitan, a black, disabled athlete and TV presenter, who said: “As someone who grew up never seeing himself in a book, this is something that is really important to me. I rarely saw a disabled character, and where I did, it was a negative one. I realised I could do something really valuable” (Strick, 2018). By not having literature to empathise and connect to as a child, Adepitan is producing literature to allow others to connect with his own experiences (Strick, 2018). “Energies must be invested into normalising and making mainstream the breadth and range of realities that exist within our classrooms and society in order for all children to feel valued and entitled to occupy the literary space” (CLPE, 2018, p. 9). It is likewise important for children to see that people of ethnic minorities can be authors and illustrators in order to “internalize that all populations are valued in the publishing world” (Feelings, 1985; Roethler, 1998 cited by Koss, 2015, p. 33).

Unfortunately the effort to diversify authors and literary content, including the incorporation of disabilities, continues to be underrepresented within the children’s literature field. Therefore, in order to make sure that all children feel welcome when they open a book, “We need books that proclaim the territory of childhood belongs to all children” (Alam, 2016 as cited by Pennel, Wollak & Koppenhaver, 2018).

3.2.2 Representation of minorities within children’s literature

There is an apparent lack of diversity within children’s literature. According to a report made by Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE), only 391, which is 4% of the 9115 children’s books published in the UK in 2017 contained black, Asian and minority ethnicities (BAME) characters, despite 32% of compulsory school children in England being of minority ethnic origins (CLPE, 2018, p. 7). It is important to increase the number of inclusive books that educate the differences in people’s lives; “Literature that reveals cultural nuances among racial/ethnic groups could empower both children from ethnic minority groups and children from the dominant culture to understand the complicated nature of human experiences and the social constructions of race and identity” (Monoyiou & Symeonidou, 2016). It is likewise important for children’s literature to more fully represent BAME characters, as this would create a more accurate and meaningful representation of diverse populations within the UK (CLPE). One example is Knights Of, an independent publisher and bookshop, which focuses on the easy availability of books featuring only BAME protagonists in a London bookshop (Flood, 2018).

CLPE’s report highlights that of 391 books included in the report, almost a third of them contained themes of social justice, “which very much corresponds with the societal context of recent years and is important to acknowledge, explore and mirror in literature” (CLPE, 2018, p. 5). However it does theorise whether the inclusion of themes related to minority backgrounds within children’s literature can only occur when exploring suffering and struggles within a societal context. Indeed, only one book featuring BAME characters was classified as comedy, which could suggest that books featuring BAME themes tend to centre around serious topics and away from comedic or enjoyable scenarios (CLPE, 2018).

Whilst it is important for children’s books to contain elements of diversity and representation of minorities, it is even more important that those representations are correct and accurate. In order to ensure the correct portrayal of themes that the author and illustrator may not have real-world experience in, they must undertake extensive research in order to avoid any stereotypes or misconceptions (Crippen, 2012). One example of an illustrator failing to conduct adequate research into the subject can be seen in ‘The Rough-Face Girl’by Rafe Martin, published in 1998. This picturebook based on Native Americans, shows the Iroquois tribe, which historically lived in longhouses (Johnson, 2003, p. 33), illustrated living in tee pees (see Figure 3.1). This not only gives a wrong impression, but provides incorrect information, which could be used later in life to perpetuate potentially damaging stereotypes (Crippen, 2012). It can therefore be evidenced that there is a desire and call for more representation of BAME minorities, as well as disability.

3.3 Disability in children’s literature

3.3.1 Representation

Picturebooks featuring disability can be designed to show a diverse range of lives that allow readers to both comprehend and learn. It is important for young readers to understand and appreciate the diversity of life when compared to their own, making them fully empathetic (Gilmore & Howard, 2016). As previously explored, the ability for a child to be able to mirror themselves in a book character is crucial as it can have positive effects on their lives, which is especially true with disability. Strick (2018) states, “Disabled kids can do anything, but in order to believe it, you have to see it”. Picturebooks allow children to experience a full range of scenarios that they would not normally encounter, or depict accurate and empowering narratives about one’s own disability, showing that people with disabilities are just as able, therefore working towards normalising disability within literature (Gilmore & Howard, 2016).

Despite good intentions, if a disabled character is misrepresented it can have a detrimental impact on the reader, as they will have to “renegotiate their misunderstanding of the nature of disability at a later date in order to successfully manage disability, whether their own or others’, in private and public life” (Saunders, 2004). An example of misrepresentation could be when characters with an inhibiting physical disability gain exaggerated strengths elsewhere to compensate for their perceived loss. This results in the narrative being focused on ‘fixing’ the disability and “trying to make them ‘fit’ more seamlessly into what is seen as a ‘normal’ society” (Dunn, 2010, p. 16 as cited by Adomat, 2014). Consequently there could be certain challenges that rise when representing people with disabilities in literature, especially if the author or illustrator has no first-hand experience of disability. Furthermore, the fear of patronising or accidentally causing offence, whilst appropriately representing disability in a sensitive manner, can be tricky. In other words, it could be argued that the lack of disability represented in the literature is due to authors and illustrators being apprehensive to write about such topics.

Overall, realistic depictions of disabled and non-disabled characters can positively assist children in becoming familiar with the reality of disability in authentic ways. This will help non-disabled children learn to understand and accept their disabled peers, whilst teaching children with disability to understand themselves better and show that they are just as capable as the dominant culture (Monoyiou & Symeonidou, 2016).

3.4 Language used to describe disability in children’s literature

3.4.1 ‘People first’ language

To illustrate communicating disability through spoken and written language, there are a number of elements to take into consideration. ‘People first’ language is one approach used to appropriately and respectfully refer to people with a disability by counteracting cultural stereotypes to ensure the individual is put ahead of their disability (Adomat, 2014; CDC, 2019). An example of this might be “a person who has visual impairment”, rather than “visually impaired person”. By putting the person first, it enables their identity to be defined by who they are, not their disability, which in turn becomes just another part of a their life.

However, there is a debate around etiquette and the use of such language when referring to people with disabilities. The academic blogger Crippledscholar argues that there can be cultural disparities between the use of some words and phrases, due to the perception of how a disability affects an individual (CrippledScholar, 2015). They say that: “In North America disability is mostly defined in society through a purely medical perspective. Disability equals a disease that must be stopped and is the source of suffering in the individual” (Crippledscholar, 2015). This might connect disability with negative connotations, potentially increasing negative judgement and stereotypes. Therefore, by encouraging the use of ‘people first’ language, it may assist in humanising individuals.

3.4.2 Acceptable and unacceptable language

With the development in ‘people first’ language, it is also critical to understand what vocabulary is acceptable to use, and its change over time. Due to the increase in social awareness, words that were once unquestioned in their use to describe people with disabilities may no longer be acceptable. An example of the evolution of language is referred to by Gilmore & Howard (2016) when they encourage adult readers of the picturebook ‘What’s Wrong with Timmy?’ by Maria Shriver to replace terms that are no longer appropriate, such as “mental retardation”, with more suitable substitutes like “developmental” or “intellectual disability” (Gilmore & Howard, 2016, p. 36). Using appropriate language when describing or talking about people with disabilities creates equality, whereas inappropriate language may cause offence (Disability Resource Centre, 2019); it is therefore important to be aware of words and phrases to avoid. Figure 3.2 displays a table produced by the UK Government to highlight words and phrases that should be avoided and suggest more appropriate ways of referring to people with disabilities.

Cambridge University’s Disability Resource Centre (DRC) also offers a collection of language and etiquette to consider when interacting with and referring to a person with a disability. In both the DRC and UK Government guidelines, “the disabled” is identified as a term to avoid, offering “disabled people” as a more appropriate alternative (Disability Resource Centre, 2019; GOV.UK, 2019b). When looking at these guidelines, it is evident that they do not use ‘people first’ language. Booktrust, a charity dedicated to getting children to read, does not abide by ‘people first’ language either it suggests using the term “disabled person” as opposed to “person with a disability”. This gives a good indication of how difficult it is to decide what terminology is acceptable when referring to disability as people will respond to terminology in their own way, often having a preference for their own use that might be not the same as general guidelines (CrippledScholar, 2015). This could be due to ‘people first’ language, and the suggestions given by DRC and the UK Government being merely guidelines to raise the base standard for acceptable language, educating people who may not have encountered disability in their lives and need assistance in referring to it in a respectful way.

Despite this confusion and ambiguity with regards to languaget, there are some words that should be completely avoided. As Saunders (2004) points out “their description of protagonists being “imprisoned” in their wheelchairs, “wheelchair bound” and “crippled” indicates that the affirmative language preferred by disabled people has been overlooked and suggests that their analysis may not have been informed by other contemporary ideas about disability.” As a general rule, avoid phrases like ‘suffers from’, as this “suggests discomfort, constant pain and a sense of hopelessness” (GOV.UK, 2019b). Likewise people who use a wheelchair may not consider themselves “‘confined to’ a wheelchair”, but rather the wheelchair enables their independent mobility (GOV.UK, 2019b).

On the whole, the language used to describe people with disabilities is encouraged to be personal as to retain their humanity over a condition, whilst also avoiding “strange or exotic” in order to ensure the disability is not viewed as an abnormality (Booktrust, 2019b). Although language like this is supported, it must also be recognised that individuals with a disability will continue to determine their own personal preference for the language used to refer to them (CrippledScholar, 2015).

In this dissertation, the researcher will be using ‘people first’ language when referring to people with disabilities, as it offers the most respectful approach, considering the researcher is not a part of the disabled community. The research will examine further how far this approach to language has been taken.

3.4.3 Visual Language

In the case of most books, Salisbury & Styles (2012, p. 81) note that the words will carry the story, but picturebooks are one of the few book genres where the pictures and illustrations are equally, if not more, important. Furthermore they argue that children look for more than just a story when they pick up a picturebook, “so it is not surprising that, when faced with complex multimodal texts, they puzzle over what the pictures might symbolize or how words and images together construct meaning” (Salisbury & Styles, 2012, p. 81). Fundamentally, by acknowledging the “fusion of words and images that is key to the picturebook experience” (Salisbury & Styles, 2012, p. 50), the story behind the pictures gives a greater depth to the narrative, leading to further activation of the reader’s imagination.

Previous points raised in this dissertation regarding representation and inclusion of disability within picturebooks linguistically, can also be translated to visual language. Comparisons can be drawn to the appropriate use of representing disability through illustration, as it is important that it is done correctly. There have been calls for illustrators, most notably author and illustrator Quentin Blake, to take greater consideration of when, where and how they include disability in their work: “We can’t have a quota and we can’t have a token. But one day I hope it just comes naturally, it’s not something I would have to think about” (Monaghan, 2014).

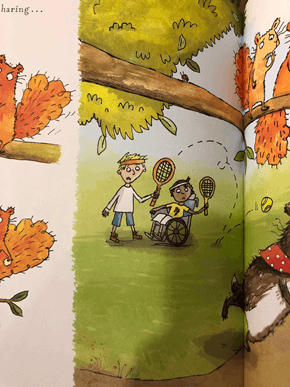

Incidental inclusion could be one answer to Blake’s desire to subconsciously include a more diverse range of characters in picturebooks. This is where a character in a book, be that a protagonist or background character, is illustrated with a disability – or as part of any other minority group that is underrepresented – without it necessarily being acknowledged in the storyline (Booktrust, 2019a). However, it is not always easy to include disabilit. Author and illustrator Steve Antony was told to “lose the wheelchair” or at least take it off the cover by publishers when presenting the first draft of his book ‘Amazing’. The reason he was given was that it would be a “hard sell” (Antony, 2019). Antony suggests that authors and illustrators of picturebooks should create more incidental inclusion of disabilities and other minorities in their work: “Just pop some same-sex parents in your bustling street scene, or add more ethnic minorities to your picture of a playground, or include a wheelchair user in your drawing of a train station” (Antony, 2019). Including instances like this would illustrate disabilities and wider minority figures in more natural ways, working towards these characters becoming more common place in children’s picturebooks, be that in a main role or part of the fictional world.

This shows just how important it is to get the visual language and overall language correct when writing about disability, as the illustrations are an equally large part of these books, supporting and sometimes leading the written narrative. Furthermore, as children’s literature has a strong value to a child’s development, representation needs to be correct and appropriate so as not to distort young readers’ perceptions of disability. By understanding these topics the researcher can now apply the knowledge and understanding of fair and accurate representation and inclusion to research, checking to see how, in practice, the extent these theories are applied to children’s picturebooks in reality.

4. METHODOLOGY

4.1 Research goals

In order to produce the most relevant and supportive results, the researcher used social approaches, such as mixed methods to “produce a more comprehensive account of the thing being researched” (Denscombe, 2017, p. 175), creating a well-rounded depiction of the research. This included both quantitative and qualitative data taken through various first person inquiries including the observational analysis and content analysis, as well as interviews – both face to face and online. During the observational and content analysis, the researcher began with gathering qualitative data from the samples, which allowed detailed observations of the inclusion and language of disability to be taken from the picturebooks sampled. Using qualitative data allowed the researcher to go into greater depth with the study and provided the best possible understanding of the sample. At this stage of the study, the researcher did not know what the findings of the content analysis would be, which made it difficult to gather specific quantitative data around disability inclusion and representation. From here, through analysis of the data gathered, it was possible to spot themes, patterns and trends in the research, which enabled an evaluative use of quantitative data to assist in drawing conclusions. This was beneficial as it allowed the researcher to gain insight through graphical interpretation.

The overall research is made from three separate designs:

- Observational analysis to observe how often disability is included in picturebooks.

- Content analysis, to explore the use of language and illustration in books featuring disability.

- Interviews, providing professional insight into the publishing industry and its connection to children’s picturebooks featuring disability.

With each stage of the research, the field of view is narrowed to draw data across all aspects of children’s picturebooks. The observational analysis allows a wider review of all children’s picturebooks, whilst the content analysis inspects specific aspects of qualifying components, and finally, the interviews allow for a highly targeted review of disability within children’s literature.

4.2 Research design methods

4.2.1 Observational analysis

The researcher undertook social research, in the form of random sampling in order to get a conceptof the level of inclusivity of physical disability within children’s picturebooks. According to Denscombe (2017, p. 36) “with random sampling the inclusion of a person in the sample is based entirely on chance. Random selection ensures that there is no scope for the researcher to influence the sample in some way that will introduce bias”. Using this method of sampling meant that the researcher could go into the research with no preconceptions of the books sampled.

The population of study was limited to picturebooks on the shelves in the relevant children’s picturebook section in Waterstones Piccadilly. The researcher picked this particular bookshop as Waterstones is the biggest dedicated bookseller in the UK and the Piccadilly store the largest in its chain. No further restrictions were made as the researcher wanted to keep the sample unstructured in order to get a realistic portrayal of how common disability is within picturebooks.

Over the course of four hours, the researcher sampled 54 picturebooks to explore to what extent these publicly available books contained physical disability. They were read in their entirety in order to observe the visual and written language, with observations being made of any inclusion of physical disability; purposeful or incidental. All physical disabilities were sought, including characters with supportive apparatus such as: hearing aids, wheelchairs, tinted glasses, walking sticks and other indicators of a disability. Whilst collecting data, the researcher collated the findings into a spreadsheet in order to assist in the data analysis. Information such as book title, author name, illustrator name and ISBN number were also recorded. The researcher took images of any pages that included disability for referral at any later stage if needed.

When analysing the data, the researcher first reviewed the number of books in the sample, calculating the number that did and did not feature disability. Using these totals, percentage calculations were made to find what percentage of the sample featured disability. Furthermore, the qualitative data gathered regarding the type and course of inclusion was analysed. Finally, connections between the year of publication and its relative inclusion of disability were correlated to determine if there was any link between the book’s age and its connection to disability. Charts and graphs were then made to easily display the data.

Whilst conducting this study, limitations were faced when selecting the sample from the study population. The researcher was constrained by the available stock displayed on the day, which may have varied from the wider Waterstones’ stock. Furthermore, due to Waterstones being a leading UK bookseller, this selected sample may not have featured some authors from independent publishers and international markets. For these instances, the researcher will ensure to reflect on the findings as a single study with various parameters out of their control. Although a random selection process was decided upon, in hindsight, the way the sampling was approached was not entirely random, due to human factor of personal choice. Upon reflection, it may have been more appropriate to approach the sample in a systematic way, selecting every nth book on the shelf.

4.2.2 Content Analysis

“Quantitative content analysis captures particular features of text by categorizing parts of the text into categories, which are operationalizations of the interesting features. The frequencies of the single categories inform features of the analysed text” (Flick, 2015, p. 164). For this dissertation, the researcher undertook content analysis in order to assess if representation of characters with physical disabilities was accurate, appropriate and respectful within children’s picturebooks. As part of the content analysis, the researcher reviewed the books for both literary and illustrative accounts of disability, noting any qualitative data that fulfilled a specific range of criteria to best overview and analyse the books. From this, quantitative data can be produced, drawing from common themes, trends and observations across the sample.

The researcher collected 17 picturebooks featuring varying extents of physical disability, that were distinct from the books sampled within the observational analysis. The goal whilst collating the sample was to feature books that had a strong sense of physical disability, as this would allow the researcher greater ability to analyse and deconstruct the contents. Furthermore, the date of publication was not limited, as to do this would have inhibited the selection.

The majority of the sampled books were purchased from online retailers, predominantly Amazon.co.uk, whilst only a small number were sourced from physical shops. In order to analyse the content, the books were read in their entirety and images studied for relevant depictions. From here, this qualitative data was recorded in a spreadsheet, as well as data regarding the publication of the book. Visual and written language was assessed for types of disability and attitudes towards the featured disablements as well as data regarding the link between the disability and overall narrative.

The qualitative data from the aforementioned spreadsheet was assessed to produce quantitative data, therefore providing the ability to produce graphs and charts. This then allowed the researcher to overview how many of the sampled books included the criteria tested enabling conclusions to be made based on this data.

The main limitation presented at this stage of research was the lack of availability of picturebooks advertised as featuring a disability. Whilst the researcher was building a collection of titles to analyse, it was increasingly difficult to find relevant and accessible books that featured a physical disability. Searches of physical and online stores from some of the largest booksellers proved mostly unsuccessful. The researcher collated the books from a range of sources, discovering them in a variety of ways, mainly through recommendation. The researcher would have hoped the observational analysis would have yielded more books prominently featuring disability to use in the content analysis.

4.2.3 Interviews

The researcher conducted an in-person interview in a semi-structured format, in order to gain knowledge in the participant’s opinion on the inclusion of physical disability in children’s picturebooks. Flick (2015, p. 140) describes the aim of such interviews as “to obtain the individual views of the interviewees on an issue”, which can be directly applied to the researcher’s intent. In order to further build upon the researcher’s findings, an online interview was conducted with two other participants via email.

The target population for the study was individuals working within publishing, ideally editorial or book creation, who were responsible for approving books to be published or creating the text and images. The researcher theorised these individuals would be able to give a good insight into the extent to which the publishing industry includes disability in picturebooks.

The interviews consisted of a mix of open and semi-structured questions. Open questions allow “room for the specific, personal views of the interviewees and also avoid influencing them” (Flick, 2015, p. 141), while semi-structured questions “introduce issues the interviewees would not have mentioned spontaneously” (Flick, 2015, p. 141). Data was collected through a face-to-face interview and online email questioning with participants. The researcher was able to meet one of the participants in person in order to create an open dialogue. For the online interviews, the participants were contacted through email in order to agree to take part and then sent questions to answer. During email questioning, an asynchronous approach was undertaken (Flick, 2015, p. 202), where all the interview questions were sent to the participants and they return all their answers at the same time. “Like face-to-face interviews these kinds of interview retain a basic question and answer sequence” (Denscombe, 2017, p. 2017). No closed questions were included in any interview, as this would discourage dialogue between the participant and the researcher. The researcher also made the interview questions opinion-based to ensure participants would not speak on behalf of someone else.

The qualitative data from the interviews was analysed in order to draw any repeating trends or themes. Consequently, the responses were analysed to see how they agreed or disagreed with each other with their words being used to draw conclusions and pose further questions.

Although effort was made by the researcher to conduct expert interviews with relevant people from the publishing industry, this was partly unsuccessful due to the busy schedules and limited time available from people within editorial. Conducting an expert interview with someone working directly within a publishing company would have been preferable as the researcher would have been able to ask about the motivation behind the inclusion of disability. In addition to this, the main limitation faced when interviewing via email was be the lengthy time delay between the initial establishing of the interview and receiving the answers; the researcher did have to follow up onthe participants to ensure answers would be received in time to finish the dissertation. Another significant limitation was the lack of flexibility during email interviews to pose follow-up questions in a timely manner. The absence of visual contact also meant the researcher had “less opportunity to confirm the identity of the interviewee or verify the information given by that person” (Denscombe, 2017, p. 2017). Finally, due to the lack of available time the interviewees could commit to this research, the amount of questions sent to the email participants varied, as seen in appendix E, G and H. For one email contact questions were limited to four, which meant reducing the interview to its core. It was only possible to conduct one in-person interview with one participant due to time pressure and geographical constraints.

4.2.4 Overall combination of analytical approaches

Through each research method the researcher was able to build upon the sample and findings. The observation analysis was designed to sample a broad collection of picturebooks, whilst the content analysis intended to take the findings from the previous investigation and review these in greater detail. By then gathering focused data from specific books, the researcher could then progress the findings one step further to develop interview questions with relevant subjects relating to the content analysis. By developing each method to the next, the researcher provided validity by investigating themes and trends through each step of the research.

4.3 Consent ethics

All interviewees in this dissertation participated voluntarily, agreeing to offer their opinions to aid the research. For the in-person interview conducted by the researcher, an adapted consent form was developed to further clearly outline participation and how personal data was to be used (see Appendix F). Under General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the use of personal data must be granted, made more prominent by the researchers intention to record audio from the meeting to aid in transcription and referencing (EU GDPR, 2019). As outlined by Denscombe (2017, p. 347) a consent form does two things: “it provides the potential participant with enough information about the research and their involvement for them to make an informed decision”, as well as providing the researcher with written consent that the participant agreed to take part. Overall, the concept of no harm was upheld and the needs of all participants were taken into careful consideration during the research stage of this study.

5. FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS

5.1 Theories

For this dissertation, the researcher undertook the aforementioned methods of research to develop primary data around the dissertation subject. The research was designed to test various theories in order to build a more comprehensive understanding of the topic and finally being able to support concluding statements in response to the subject question. Within this section, the researcher will present their findings, analyse and reflect on process and results. Each method of research has its own purpose towards answering the topic question.

5.2 Observational analysis

Ahead of conducting the observational analysis in Waterstones Piccadilly, the researcher theorised that books featuring disability would be hard to find and not commonly accessible. The researcher also theorised that there would be no separate highlight within the shop towards children’s picturebooks promoting physical disability, as well as disability as a whole. Finally, it was theorised that if disability was to be included it would most likely be in the form of people using wheelchairs.

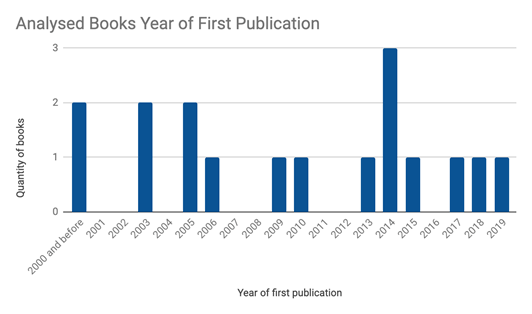

The researcher randomly sampled 54 books from the shelves of Waterstones Piccadilly (Appendix A), testing for their inclusion of physical disability, with findings presented below (see Figure 5.1).

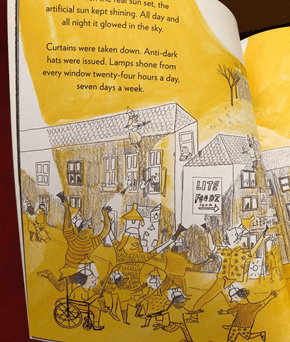

Based on the observational analysis in Waterstones Piccadilly, only five (9.3%) of the books sampled featured physical disability, whereas 49 (90.7%) did not. This supported the researcher’s hypothesis that there is a major lack of disability featured in children’s picturebooks. For this data, a pie chart was used to represent the split in the whole sampled population, with the addition of the numerical key giving further depth to the chart allowing it to visually and numerically represent the data. Furthermore all of the five books featuring disability did so through incidental inclusion of characters using wheelchairs in the background of a scene (see Appendix B). This also means that none of the books sampled included disability as part of the main narrative or prominently within the imagery. It is important to have disabilities featured incidentally as part of the wider populations, however it could be suggested that only including people using wheelchairs could cause a damaging effect to people’s understanding of what disability is.

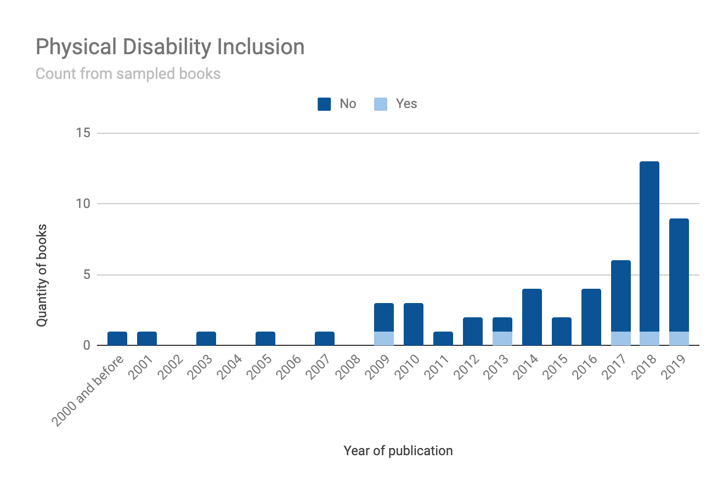

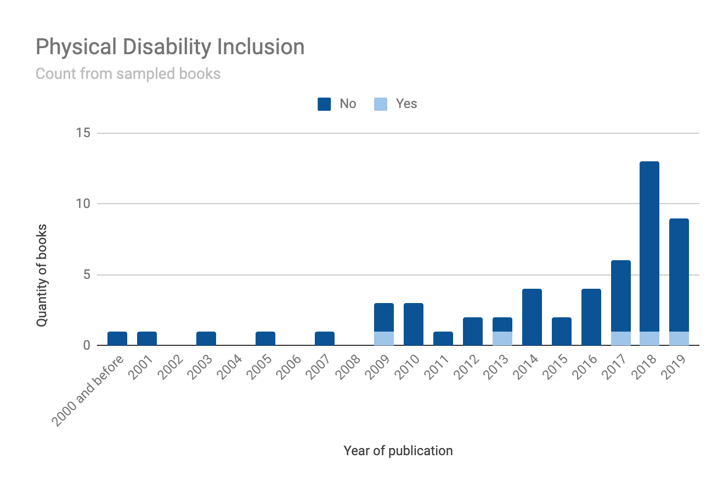

Figure 5.2 shows the number of books sampled, plotted against the year in which the books were published, plus detail on whether those books did (Yes) or did not (No) include disability. The majority of the books sampled were released over the past year, with more books in 2018 than 2019. The reason for this was because the research was conducted at the beginning of March 2019, only three months into 2019, which did not allow time for new picturebooks to be released. As seen in the chart, only five books out of the sampled 54 contained a disability. These books were published in 2009, 2013, 2017, 2018 and 2019. The fact that the researcher was able to find one book released within the first three months of the year featuring a disability could be seen as a positive as it could be believed that more books will follow suit throughout the rest of the year. Given that there were books featuring disability released during the past three years, it indicates that disability is being included more frequently. It could, therefore, be argued that this is showing an increase in disability representation, although it still remains a very small fraction of the population. However this, aligned with the researcher’s initial hypothesis of books containing disability being difficult to find, has evidenced that it is at least possible to obtain such books.

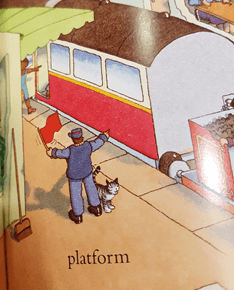

As observed in Figure 5.2, one book featuring a disability was released in 2009 and sits as an outlier to the rest of the data representing inclusion of physical disability. When reviewing this fact, it may be concluded that the inclusion of physical disability could have been revolutionary in its time, as disability representation may have been a lot less publicised in 2009. Upon reviewing the specified book, ‘Little Red Train: Busy Day’, it had only one instance of disability featured: a male using a wheelchair (see Figure 5.3). This character is physically and medically disabled, but is not affected by social disablement due to the inclusion of a ramp to the station building (see Figure 5.3). However, as seen in Figure 5.4, there is no visible ramp to the train, meaning that the character may encounter social disability due to the societal barrier of being unable to climb onto the train unassisted. This is a good example of the inconsistency in defining disability through social and medical definitions, as originally raised in section 2.1.

Drawing from the findings in the observational analysis, it is clear to see that physical mobility disabilities requiring the use of a wheelchair is the only type of disability included in the sampled books (see Appendix A). This can be seen as a positive step forward, but questions why only this form of disability is included.

Overall, based on the observations, it is clear to see that disability inclusion within children’s picturebooks is minimal. The researcher had not anticipated finding any books containing disability, therefore these findings can be perceived as positive. However, it can be questioned how many books would need to feature physical disability in order for it to be widely represented. It must also be considered that had the researcher continued the study to include all the picturebooks within Waterstones Piccadilly, the percentage of inclusion may differ.

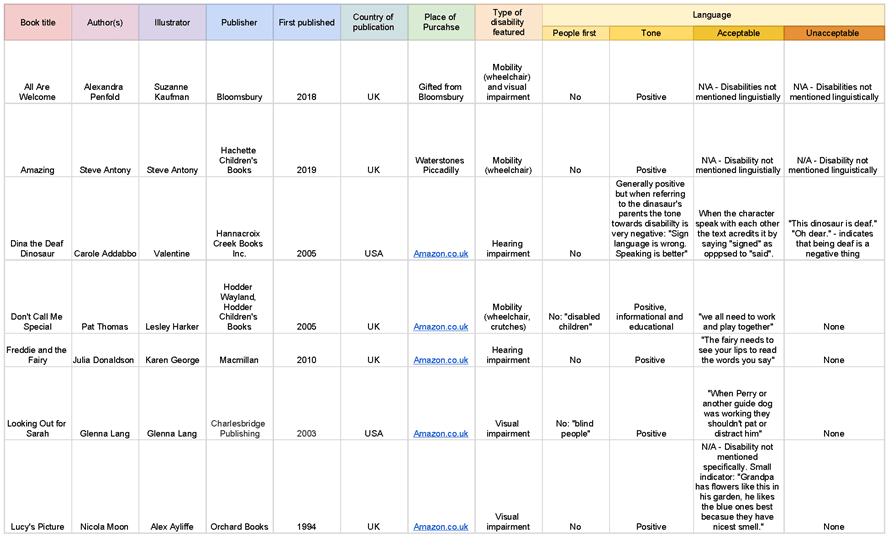

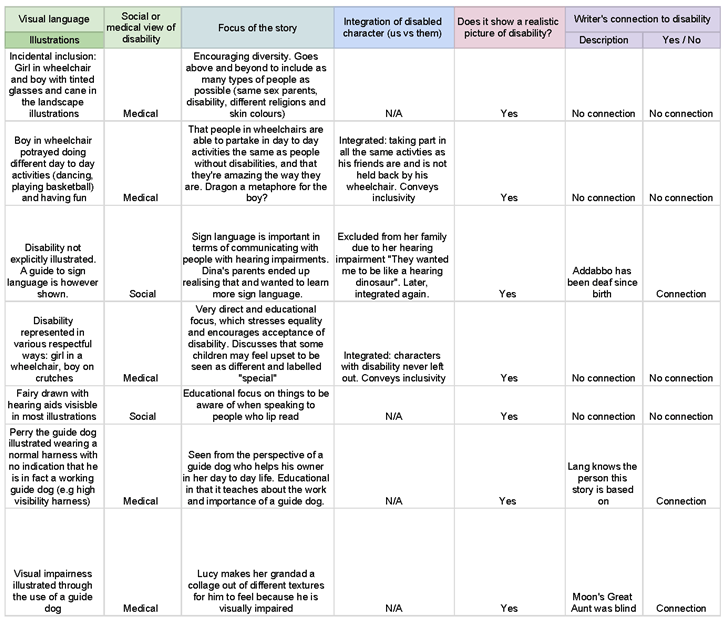

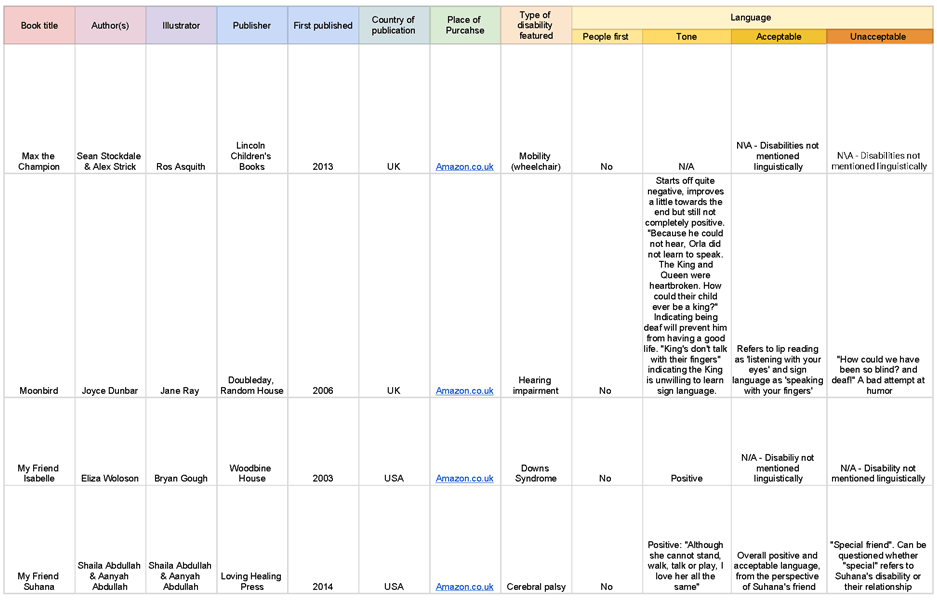

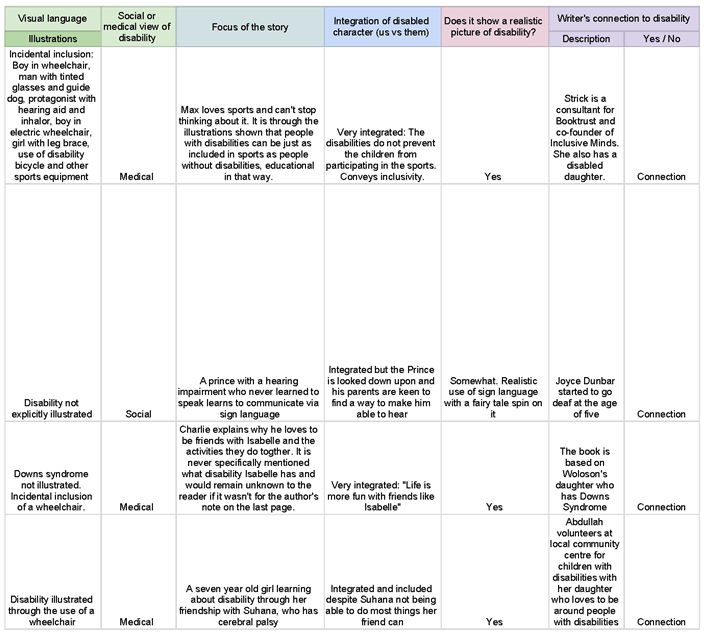

5.3 Content analysis

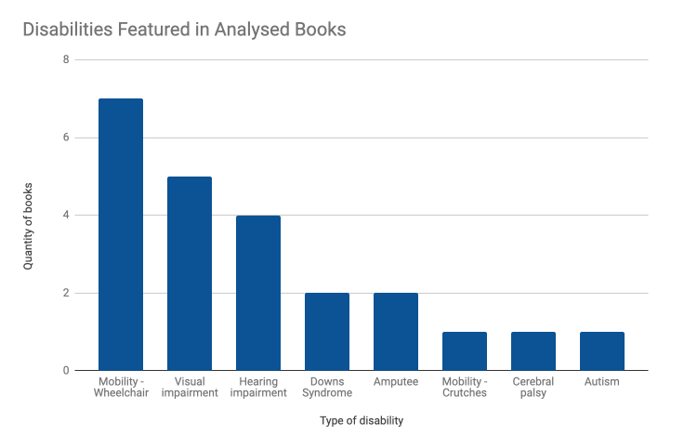

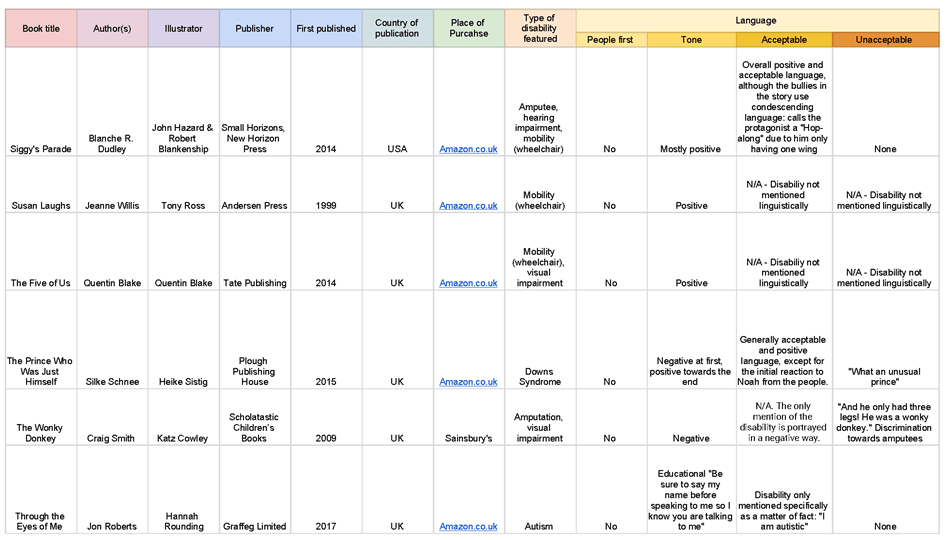

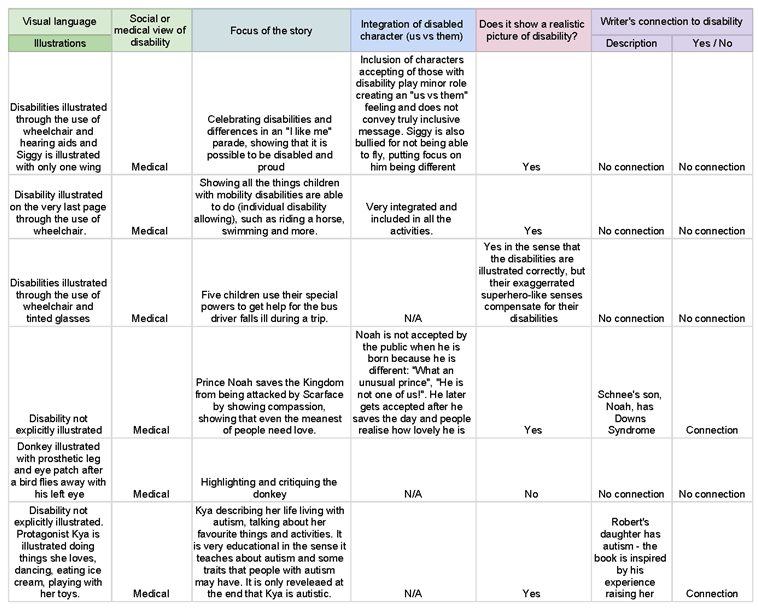

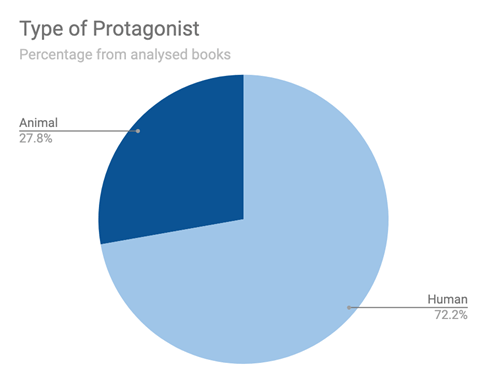

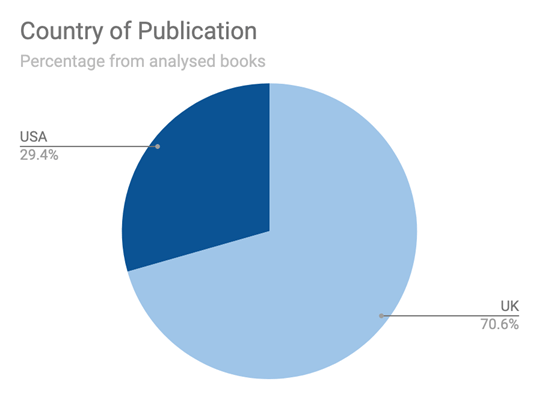

For the 17 books selected to analyse as part of the content analysis, the researcher looked for picturebooks that were centrered around disability, or had a character’s disability as a prominent part of the story. Through this analysis, the researcher further reviewed and tested the books in an analytical way. It was hypothesised that the books would accurately represent and portray disability, as well as having a positive approach to the subject matter, indicating that the publishing industry is working positively towards greater inclusion of disability within the picturebook market. The books analysed featured various kinds of physical disabilities, including mobility disablements, visual impairment and Downs Syndrome, as fully outlined in the content analysis table in Appendix C. Figure 5.6 totals the inclusion of these disabilities represented across the sample in order to clearly review the commonality of each disability. There is a clear indication that mobility disabilities that cause a character to use a wheelchair is represented the most. Following this, visual and hearing impairment are also represented a considerable amount. It could be concluded that recognisable physical apparatus such as wheelchairs, guide dogs and hearing aids are easier to illustrate to a younger audience, than sometimes more complex conditions such as Cerebral Palsy; only featured once in the sample analysed (Figure 5.6). This is further evidenced when reviewing the book ‘My Friend Suhana’, where the inclusion of Cerebral Palsy is not clearly seen by the illustrations (see Figures 5.7 and 5.8), but instead being included through the language used.

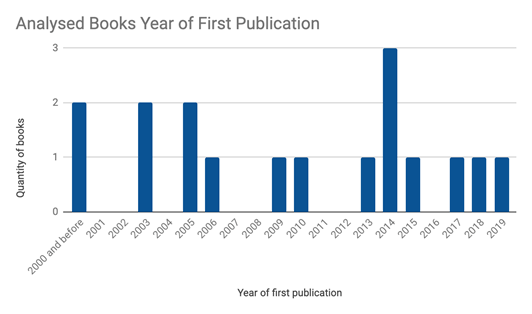

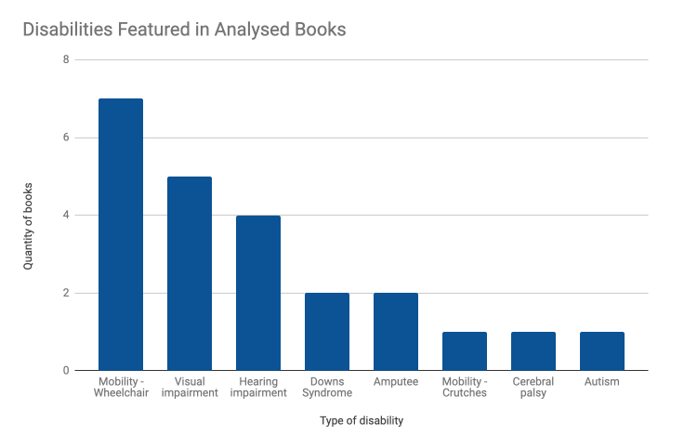

When correlating the year of first publication of the 17 analysed books, it is seen that there is no clear trend as seen in Figure 5.9. However, the sample of 17 used within this analysis was too small to be able to draw any wider industry conclusions. The range of publication dates was large, with a slight weighting towards books from the last 10 years. This was evident when the researcher was compiling the sample for the content analysis, as finding books that prominently featured disability was challenging. As seen through the observational analysis, the researcher did not find any books that prominently featured physical disability. However, one book was purchased from the observational analysis location after a recommendation from a member of staff. On the whole, the majority of books used for the analysis were purchased from Amazon.co.uk due to the challenges faced when identifying books about physical disability in stores (see Appendix C). It could be suggested that this is common as previously seen in Section 2.3.1 and Figure 2.1, where most books bought for ages 0-13 year olds were bought on Amazon.co.uk.

When evaluating the range of analysed books, a focus was put on various elements of language as seen in Appendix C. None of the books made use of ‘people first’ language, as described in the Section 3.4.1, however mostly respectful terms were used in its place. The overall tone of the books was good, with the exception of a few which addressed some negative connotations with regards to the disability featured. One example is ‘Dina the Deaf Dinosaur’ where the protagonist’s parents react very negatively towards the deafness of Dina, “Sign language is wrong. Speaking is better” (Addabbo, 2005). In another instance in response to the observation that Dina was deaf, a character says “Oh dear” (Addabbo, 2005), indicating that being deaf is something that warrants pity. Despite some negative language, the book also included some positive terminology by using “signed” rather than “says” whilst Dina talked to her friends using sign language (Addabbo, 2005). This showed that despite some of the characters being given critical attitudes, the actual writing of the book stemmed from a positive and inclusive stance, which could be concluded was due to the author of the book being deaf herself since birth.

An example of a solely positive tone can be seen in ‘My Friend Suhana’, “Although she cannot stand, walk, talk or play, I love her all the same” (Abdullah, 2014). It is also worth considering here the author’s relationship to disability,as Shaila Abdullah, author of the book is connected to disability via her daughter forming a strong bond with a friend who has Cerebral Palsy. In this instance, ‘My Friend Suhana’is a reflection on true events and the relationship that can form, irrespective of any physical disability.

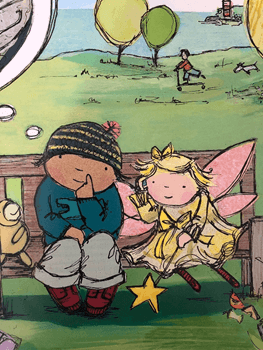

Throughout the analysed sample, there was a range of visual language used to illustrate disability. Some of the featured books did not clearly illustrate disability, for example ‘My Friend Isabelle’ and ‘The Prince Who Was Just Himself’ depicted characters withDown’s Syndrome,which in both cases did not affect the character in a visual manner. However, Julia Donaldson’s ‘Freddie and the Fairy’features a character with a hearing impairment, physically represented by a small and subtle hearing aid worn throughout the book (Figure 5.10). As this book is illustrated stylistically, the inclusion of the hearing aid is not life-like so has been interpreted to fit the style of illustration.

With regards to a realistic depiction of disability, the majority of the analysed sample represented the disability accurately through visual and linguistic language. However, Quentin Blake’s ‘The Five of Us’includes compensation of disability through exaggerated ability such as one of the characters’ ability to hear a bird sneeze five miles away, whilst also being blind. Such compensation could be seen as problematic and as something that should be avoided, as outlined in Section 3.3.1.

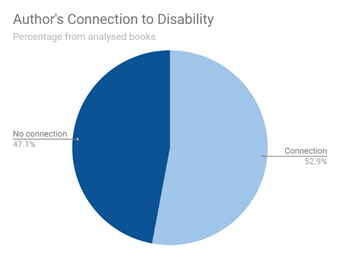

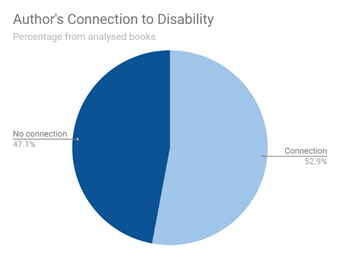

The researcher theorised that authors would be writing about disability as they had a connection to it in their own life. Although this theory may be hard to prove due to authors not disclosing why they might write a book, the researcher found that eight of the books featured a small author’s note explaining the disability and/or the connection the author had to the subject. Figure 5.11 shows the relationship the authors of the 17 sampled picturebooks had with disability. It can be drawn that there was almost a near 50/50 split between a connection to disability and not. This is a progressive step towards the overall dissertation question as it shows authors are able to write about disability, even if they are not touched by it. Furthermore, it is something that can be freely written about, not just left to those who feel connected to the subject in order to write about it. For authors that have no known connection to disability, on the whole they represented characters respectfully and correctly.

5.4 Interviews

The responses to the interviews consisted of a number of key trends in the opinions presented by the interviewees. Each participant offered a varying view on the publishing industry, with overall commonalities; but in some cases slightly conflicting opinions. Some of the common topics that arose in their answers overviewed the lack of diverse physical disability representation within children’s picturebooks. The interviewees also expressed opinions around correct and appropriate representation of disability, whilst some questioned the commercial aspect of the publishing industry; they also expressed how they thought the industry could do better.

5.4.1 Representation

The interviewees from Inclusive Minds, Beth Cox and Alexandra Strick expressed their concern when questioned around the extent of the publishing industry’s disability inclusion, “We do not feel that the publishing industry is specifically encouraging increased representation of disabled characters in books” (Appendix H). This was further echoed by Shaila Abdullah, who also noticed “an alarming gap in children’s literature dealing with disability” (Appendix G). These opinions aligned with the researcher’s original hypothesis.

5.4.2 Commercial

One potential reason for a lack of disabilities featured from publishers could be due to a commercial thinking as to what might sell best. When asked to comment on the observational analysis from Waterstones Piccadilly, Cox and Strick highlighted that “only a limited number [of books] make it into Waterstones” and that Waterstones might “choose the most commercial”. This led to a further question regarding whether books featuring disability in a prominent way could be considered commercial. In the same way, Cox and Strick theorise that books featuring disabled characters might be published by smaller publishers, rather than larger companies who have a higher chance of being stocked in Waterstones (Appendix H). This is furtherevidenced by Abdullah’s experience in publishing, “My sense is that publishers tend to cater to what the wider demographics has traditionally demanded and accepted when it comes to books” (Appendix G).

5.4.3 Visual language and representation

When depicting characters with disabilities for children’s picturebooks, it can be difficult to clearly define a disability in a way that a child would understand. Bridget Martin from BookTrust highlights that “there’s not much dialogue and there’s not much opportunity to describe what’s going on… Things have to be very visual in a picturebook” (Appendix E). This recognises the importance of the illustrations and can likewisebe seen in comments from Cox and Strick: “For things such as facial difference, birth marks or limb difference, illustrators may fear that people will think they have made a mistake in their drawing rather than it being intentional” (Appendix H). Overall, it is important to represent disabilities correctly, especially in a visual format such as children’s picturebooks as previously explored in Section 3.4.3, highlighted by Steve Antony.

5.4.4 Incidental inclusion

Cox and Strick suggest that “There is still a sense that books featuring disabled characters need to be ‘about’ disability” (Appendix H), resulting in authors avoiding featuring disability within their books as it could been seen as an ‘all or nothing’ situation. However, Martin stated: “in the past everybody’s just thought ‘right we need to put someone in a wheelchair if we want to include disability’” (Appendix E). This specific opinion around the use of wheelchairs as incidental inclusion is also reiterated by Cox and Strick: “There is also a misconception that the only way disability can be featured is by including a wheelchair user” (Appendix H), which is evidenced by the researcher’s results in the observational analysis. Martin further builds upon incidental inclusion by suggesting that an illustrator can build a visual scene, without including a character with a disability, “there may just be an awareness of it to the point where the building behind the action has got a ramp or a little sign about a hearing loop” (appendix E). This suggests that books like this will become noticeable as a welcoming and inclusive environment, despite not clearly adding an account of disability.

5.4.5 Future prospects

When asked about what the publishing industry can do to increase the inclusion of characters with disabilities, all participantsoverviewed various ways to develop the portrayal of disability across the industry. Cox and Strick believed that authors and illustrators needed to consider more than just wheelchair users (Appendix H). They highlighted that “fewer than 10% of disabled people use wheelchairs, so consider what else you could include” (Appendix H). Martin noted that one reason for the lack of physical disability in picturebooks was partly due to people’s ignorance in inclusion of disability, “if you’re not directly involved with somebody with a disability you may not notice it as a gap” (Appendix E). Moreover, shesuggested that fears faced by authors and illustrators may put them off including disability, as to avoid coming across as patronising and making an ill-informed mistake (Appendix E), and argued that one way to combat the lack of inclusion was to “be braver about it and don’t be held back by being scared of making a mistake” (Appendix E).

Out of all the participants, Martin was the only one who reflected positively on the publishing industry’s inclusion of disability representation, “things are changing, I think publishers are becoming more aware” (Appendix E). It could be questioned whether her positive opinion was a reflection from her own work, where she deals with progressing the positive inclusion of disability within literature, potentially making her more alert to the progression.

Finally, when asked how to bring about lasting change to the publishing industry Abdullah suggested that “the book industry needs to take a closer look at how disability is portrayed in children’s literature and facilitate accessibility and inclusion at every step. We need books that showcase positive role models who are disabled, and we need books that can facilitate a healthy discussion around interaction with disabled individuals” (Appendix G). This suggests that the publishing industry should continue to build upon the work it is doing, however it must allow greater opportunity for inclusion of all types of physical disability.

6. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

To review the original research title, it can be concluded that in most cases physical disability is represented respectfully and appropriately, although there is still an overall lack of disability inclusion of within children’s picturebooks. It was also found that these books were not easily accessible to the general public.

Upon testing multiple supplementary hypotheses, the researcher was able to develop a wider understanding of the role of physical disability within children’s picturebooks. The researcher predicted that characters using wheelchairs would be the most common type of incidental inclusion, and the researcher found this to be true based on the observational analysis. This was further confirmed by the participants of the interviews, who themselves noticed that most authors including disability seem to include a wheelchair in the background of a landscape. It was also found that the vast majority of books analysed, on the whole, offered respectful language towards and about characters with disability; there were only a few books in which the characters were portrayed using negative views of disability by other characters, despite the overall writing style and tone of the book being positive and inclusive, as highlighted specifically through the analysis of ‘Dina the Deaf Dinosaur’. Having presented evidence of what would consist of appropriate language to use when referring and talking about disability, it was clear to see that whilst inappropriate terms were avoided, linguistic styles such as ‘people first’ were not used in any of the analysed books. However, it could be questioned if authors are aware of this specific language style or if a conscious decision was made not to use ‘people first’ language.

Moreover, one of the researcher’s primary aims was to assess how accessible these types of books are to members of the public. Through the observational analysis and general gathering of sample books for the content analysis, the researcher struggled to easily access the variety of books found for other genres; resorting to sourcing mainly from online websites. It is certainly worth reflecting that whilst some books featuring physical disability can be found in physical stores, there is not yet the wealth of options provided for other books. One suggestion would be that the leading picturebook publishers encourage authors to begin writing about disability and including a greater range of physically disabled characters within their written or visual narrative. It was seen that leading picturebook author, Julia Donaldson, has written and published ‘Freddie and the Fairy’, which features hearing impairment prominently within its narrative. This is certainly a good first step that the publishing industry as a whole can take to creating fewer barriers for including disability. However, it is also worth taking notice of one point raised through the interviews that smaller and independent publishers and authors may not be afforded the same platforms as their more dominant equivalents. This means that in shops such as Waterstones, it may be unlikely to find books from these sources, making it harder to develop diversity, as publishers hold the key to introducing greater disability awareness into children’s picturebooks.

Publishers should do more to portray inclusivity towards people with physical disabilities in order to insure children with disabilities have literary characters to mirror themselves and relate to, as this could help the children with self-acceptance and understanding of themselves and others, as expressed by Koss (2015) in section 3.2.1. Increasing inclusion should be done, not by only writing about disability, but by including a variety of different disabilities in picturebooks, whether that is making a protagonist disabled or by the use of incidental inclusion in making a background character disabled. In terms of the disabilities included, the industry should ensure these characters are appropriately represented, as well as try to steer away from almost exclusively including people using wheelchairs, as the lack of variety and misrepresentation of disability could have a damaging effect on people’s understanding of what disability is, as highlighted by Saunders (2004) in section 3.3.1. Including apparatus such as hearing aids, canes, ramps or hearing loops in the illustrations of a picturebook is a simple progressive motion, that more authors and illustrators should utilise. Overall, physical disability within children’s literature remains an underrepresented minority, with a long way to go before it becomes a natural part of the publishing industry. However, it is evident that awareness of such inclusion being important is not missing completely, with some authors and illustrators developing progressive, positive and inclusive work. Following on from this research, publishers’ involvement with ensuring physical disability in picturebooks as well as the demand of these books from the general public should be explored. By developing this research, a greater understanding of the role publishers that play within this field can be gained to assess how physical disability can be more commonly featured. It needs to be explored how publishers can encourage creators to include more disability in their picturebooks, possibly looking into directly commissioning books to include physical disability.

7. BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abdullah, S. (2014) My Friend Suhana. USA: Loving Healing Press

Addabbo, C. (2005) Dina the Deaf Dinosaur. USA: Hannacroix Creek Books Inc.

Adomat, D. S. (2014) ‘Exploring Issues of Disability in Children’s Literature Discussions’, Disabilities Studies Quarterly, Volume 34, No. 3. Available at: http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/3865/3644 (Accessed: October 28 2018)

Amazon (2019) Fisher-Price “My First Books Set of 4 Baby Toddler Board Books (ABC Book, Colors Book, Numbers Book, Opposites Book). Available at: https://www.amazon.com/Fisher-Toddler-Colors-Numbers-Opposites/dp/B0128PH4T4?ref_=nav_signin& (Accessed: 27 February 2019)

Antony, S. (2019) Steve Antony: Why I’ve made the picture book they said wouldn’t sell. Available at: https://www.booktrust.org.uk/news-and-features/features/2019/february/steve-antony-why-ive-made-the-picture-book-they-said-wouldnt-sell/ (Accessed: 11 March 2019)